Here’s a quick post on the basics of outlining.

To keep it short and simple, the purpose of outlining is to organize the voluminous reading and class conversation materials generated thus far, and throughout the remainder of the semester, into a roadmap that will help you solve similar legal problems in the future using the tools of the trade. The tools most heavily tested will be your ability to methodically apply rules to facts, draw analogies and make distinctions between different scenarios, and use policy-based reasoning to break ties between equally balanced, or marginally imbalanced, arguments.

Additionally, outlining is more about the process of distilling and organizing for future use than it is about producing an information product that can be shared with other people. To be fair, producing an information product makes it possible to get outside feedback, but some individuals manage to outline without producing a shareable information product.

Distilling and organizing voluminous materials

There are several types of information contained within reading assignments and class notes. There is information about the system of law and how it functions. There is information about the people who work in and around the legal system. There is information about litigants and other people seeking dispute resolution. There are lofty think-pieces about ideals and ideal rules. There is information about the what and the whys of compromises needed to strive for the creation of a fair and just society. And finally, there is black-letter law woven throughout, whether it be cases, statutes, or models thereof.

Most of this material is necessary to become acculturated as a lawyer and to learn to operate in the profession, but it is not all exam relevant information. So with that, here are the 5 introductory maxims to outlining.

Maxim #1: Chronology of coverage does not equal conceptual order.

Sometimes, it is necessary to begin at the end so that a learner has a destination to orient upon while learning new information. So as students, just because something may have been covered at the beginning of the semester does not mean that information belongs at the beginning of your outline.

For example, my 1L contracts professor began with Section 344 Restatement second of contracts about the interests that are protected by contracts law. To summarize, these interests help courts ascertain how to calculate damages when a contract has been breached and by extension which remedies are available to litigants in contract disputes. Because we covered it first, the content lived at the beginning of my outline until very late in the semester. However, as a matter of problem-solving, identifying interests is something that happens after you figure out whether there was a contract in the first place, and if so, whether it was breached. So that content’s conceptual home is closer to the end of the roadmap than the beginning.

In my outlining workshop, to illustrate this concept with respect to outlining, I provided students an example of an issue-spotting exam question and we quickly practiced issue-spotting and then I provided a skeletal outline of an exam answer for that problem. The workshop is about the process of creating the tool to help students navigate the exam, not about the exam itself. But, unless you have a concept of what an exam will look like and require of you, the tool you create is most likely going to be mismatched to the job.

Here’s the excerpted problem I used for the workshop:

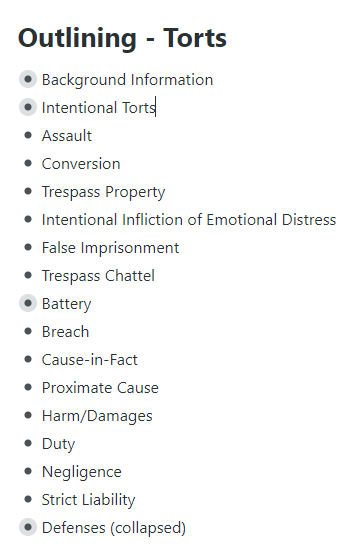

Maxim #2: The exam-relevant containers for associating like-information are “issues.”

While many law school subjects use cases to prompt students to build personal knowledge through inductive reasoning methods, exam success usually requires a student to have synthesized that information and re-organized it for deductive application on the final exam with some supplemental comparison and contrast work to support decision-making. Students read several cases to learn about concepts like battery and on the final exam are given a story that contains battery and almost-batteries to demonstrate what they’ve learned. Battery is an example of a cause-of-action level issue that students need to organize information within. In other subjects, such as constitutional law, the “issue” might not be framed as a cause-of-action, but rather as whether conduct by an entity overreaches the power granted to the entity under a certain provision of the U.S. Constitution.

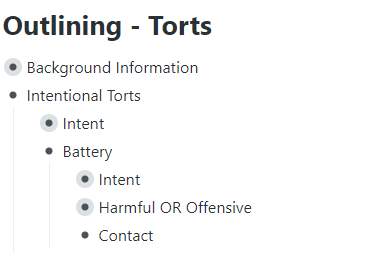

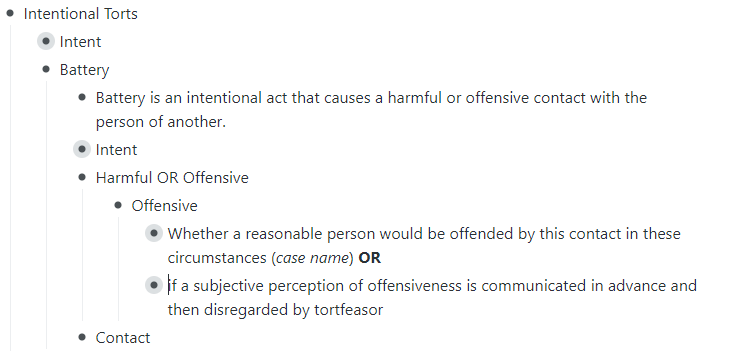

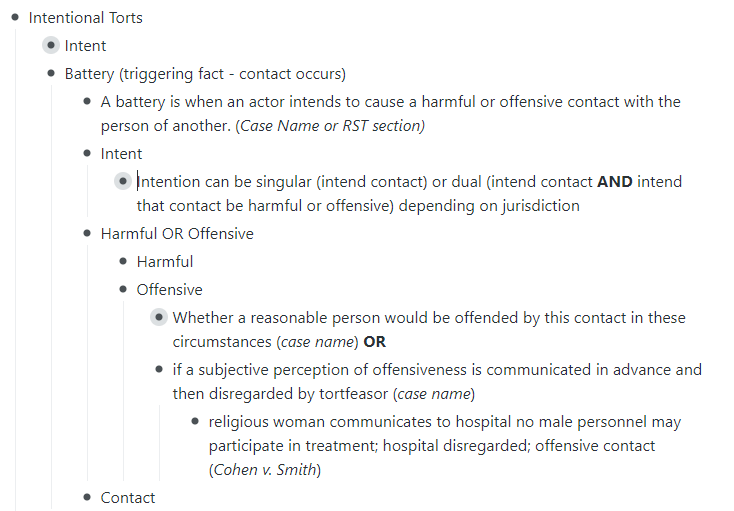

Maxim #2’s corollary: Issues can nest

While “cause-of-action” is one possible definition of what an issue is, there are sub-issues within a cause-of-action for each element. Pulling from the battery example above, once you figure out whether the story provided on the exam contains a battery or a near-battery, you have to SHOW why this is an accurate conclusion. To show your work, you have to address the elements of battery to establish whether the dispute-causer had intent to batter and did the actions of battery with enough oomph to be theoretically, legally actionable. (Oomph is a highly technical term that should never appear on a final exam unless your professor actually uses that word.)

If working in an area of law such as constitutional law, then the elements would be determined by the dissection of the relevant constitutional provision as supplemented by subsequent jurisprudence.

Maxim #3: Outlines are where you figure out how to articulate rules

Although many people believe that lawyers have to go to law school the learn rules, upon arrival it quickly becomes apparent that a lot more than memorizing lists of rules is involved. So much so, that some people do forget to focus on rules as they prepare for exams.

It’s one thing to hear that exam answers are organized by IRAC, or CRAC, CiRAC, CREAC, etc., (a common attribute of all of those is that the R stands for “rule”) and another to get to an exam and go, “now what’s the rule for battery?” Here’s a brief illustration of an IRAC (mediocre) to the first issue in the question shared above:

Outlines are where you figure out how to say a rule cleanly, and sometimes, how to say two to five different versions of the rule cleanly. For more about writing rules in informal legal writing, check out my post “Rule statements in informal legal writing, part 1.” Here’s a brief illustration of how to incorporate rule verbiage into an outline:

If you don’t spend the time figuring out rule statements prior to your exam, you’ll waste several valuable minutes figuring out how to do it during the exam, multiplied by the number of rules you need to use on the exam.

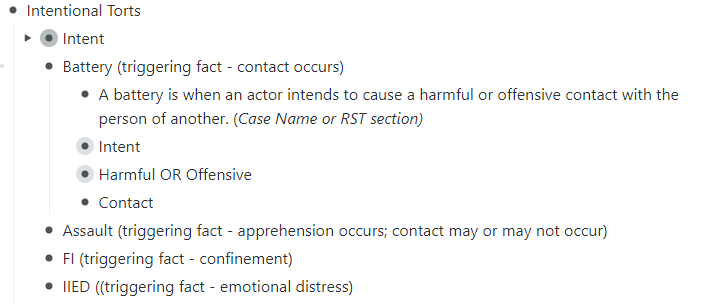

Maxim #4: For every “issue,” identify the archetypal triggering fact

Every legal issue arises in the context of facts. People do things, and legal issues arise. To successfully issue-spot, you need to know what kinds of facts in what kind of contexts between what kind of actors may lead to consequences under the rules. This is where the roadmap metaphor really comes into play.

When giving directions to others, some people use landmarks, while other people use street names with directional information, and others use some combination thereof. These archetypal triggering facts are the law school exam equivalent of “when you seen the McDonald’s across from the CVS, turn north.” They are a genericized description of a fact needed to trigger analysis of a potential legal issue under a certain rule. For example:

Maxim #5: Generally*, cases will occupy no more than three lines of your outline

*Unless it’s Constitutional Law, Criminal Procedure, or a constitutionally-based unit in a subject like Evidence or Civil Procedure. But otherwise, cases provide two things in terms of outlining. First, cases provide statements of the law for certain issues. Second, cases provide examples of when the requirements of the law under discussion have been met or not. In the example below, we see how to use a case to provide a comparison point for the subjective offense standard in a battery case.

But, what should an outline look like?

It depends. Again, some people won’t produce a shareable information product as a result of their outlining process. However, for those that do create an information product, an outline can be visualized in numerous ways.

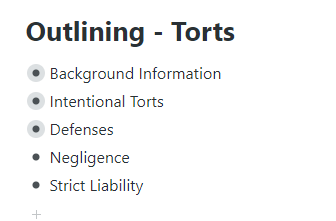

Traditional, hierarchical outlines

The traditional approach to law school outlines is to use a text-heavy, hierarchically-organized outline that either uses numbering conventions, or tabs and indentation to visualize the interrelationships between different information units. It’s a tradition that’s stuck (and is writ large through the use of the form in statutes), so clearly it works for many people. It’s also the modality I used in the screensnips shared above to illustrate the maxims of outlining.

Flowcharts & Mind maps

Some people like decision trees, and since this process is about creating a road-map for solving future problems, both flow charts and mind maps can come into play. If you’re a highly analytical thinker who can take a text and reduce it to a bunch of yes/no questions to figure out a problem, then flow charting might be the method for you. If you’re a visual thinker who likes to use proximity and illustration to see how ideas associate and work together, then mind-mapping might be for you. Here is a brief example of a partial flowchart for deciding whether to an intentional tort is present in a set of facts:

Tables

Tables can strike a middle-ground between visualization needs and the hierarchical outline. Many individuals find success by using tables for topics within a subject or for a line of cases along specific issues. Tables can be particularly useful in subjects like Evidence, Business Associations, Contracts, and sometimes Criminal Law.

What about the stuff that is not black-letter law or illustrations thereof?

Outlining is a process to personalize learning to your needs. There is no rule saying you can’t include background information. If that’s how you learn, put it in and as it becomes internalized revise your outline to be more of a problem-solving roadmap as described above. If you’re a person that really enjoys cross-text arguments, include that information in your outline, but once you confirm with the professor whether that content will be tested anywhere but the bonus questions, revise your outline to put the problem-solving roadmap front and center. If you’re a person who, for lack of a better word, hoards information, remember that some information can be disaggregated from its chronological fellows, so you can append the material you can’t bear to let go of to the end of your outline and put the material you need for exam success at the beginning.

One last thing

There are three “beats” in the life of an outline. First, a person has a voluminous amount of material that they need to sort through. Second, a person needs to organize and distill this material into internalized knowledge. Third, the organization strategy chosen needs to support the person’s ability to use the material to solve future problems within the subject area. Hit those three beats, and you’re well on your way to law school success. The methods used to hit those three beats will vary tremendously from person to person based on individual needs, individual strengths and weaknesses, and the assessment methods chosen by your professor.

More on outlining

This post focused on the basics needed for a person who is just starting law school. In the next post about outlining, we’ll talk about specific strategies for handling situations where different rules exist for solving a particular legal issue.

Recommendations/referral links

If you’re wondering what I used to create the visuals of the skeletal Torts outline, my go-to product for introducing people to outlining is workflowy.com. I started using it a really long time ago and it appealed to me because it was minimalist so I wouldn’t lose a whole day fighting with my software to make the outline pretty. I also really appreciate it’s drag-and-drop features for when I have to reorganize. It also collapses and expands content so it becomes a very useful tool for drilling memorization. And, with hashtags you can cross reference stuff in case it shows up in multiple courses.

I use Professor Chong’s book with my 1Ls and in this workshop because first, it’s an excellent and cost-effective resource for first year law students who want to incorporate practice into their study methodologies. She’s provided 8 essay questions and sample answers for 6 common first year subjects. It’s a nice, concise package of practice problems that is extremely portable. You won’t use all of them, but you will be able to use at least three from most subjects no matter who your professor is or their approach to the subject. Secondly, she’s a friend and has given me limited permission to share her work even outside of a book adoption context.